Points of Impact – Week 2: A Matter of Transition

March 2012 – Week 4

Would you look at the new logo Rich Douek made? That thing kicks such an unbelievable quantity of behind that the Mythbusters are looking into it! Thank you so much, Rich, for making this for me! I think everyone should take a moment before reading this week’s column and go have a look at the rest of his outstanding work. It’s truly worth the detour!

Welcome back to Points of Impact, the column where we don’t really review anything but you sure get to know what we think! It’s the only place on the Web where we tell you how your weekly comic haul can help you become a better writer.

As always

- The BULLSEYE! section presents something that really wowed me. That’s usually when a writer does something unique among his peers.

- The HIT! section picks up on a cool trick that gets used pretty often – mostly because it works – but of which I’ve found a prime example.

- The MISS section however isn’t about praising a good shot but – as you guessed it – pointing out where a writer stumbled so you don’t put your feet in the same hole.

Now even though these aren’t reviews per se, remember that a well-written comic always makes for an agreeable read, even though the reader might not possess the technical knowledge required to express exactly why it is so. It will simply feel right to him. That’s why creators are strongly advised to take care honing their craft as it can lead to great sale figures as much as the best marketing your publisher can afford.

Before we take the plunge, a word of warning: I get particularly spoilerific this week again so I’ll strongly advise you to go read your comics before coming back here. I’ll wait.

BULLSEYE!

The presence of seldom-used panel transitions in Robert Kirkman’s THE WALKING DEAD #95

I hope you guys brought your study caps because we’ll be delving into some heady stuff in the next few paragraphs. This week’s BULLSEYE! is awarded to a comic that dared to stray off the beaten path and into the wild territory staked out by other formats.

I hope you guys brought your study caps because we’ll be delving into some heady stuff in the next few paragraphs. This week’s BULLSEYE! is awarded to a comic that dared to stray off the beaten path and into the wild territory staked out by other formats.

In his book Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, Scott McCloud talks about closure, the reader’s mental act of filling the gap between panels with an unspoken transition that completes the meaning set down on the page by the comic’s creators. Closure is essentially what permits us to make sense out of a series of side-by-side images and enjoy them for the story they represent.

Of course, closure isn’t achieved in the same fashion every time. The type of transition the writer calls for – and that will play out in the reader’s mind – depends on the content of the panels on each side of a particular gutter (the space between panels).

Thus, McCloud lists several types of transitions. The three most common types that we see are:

- Action-to-action: This type of transition follows a single subject through a sequence of actions.

- Subject-to-subject: This type of transition asks the reader to switch to a different subject while still remaining in the same scene.

- Scene-to-scene: This type of transition requires the reader to stick to the same general idea but to switch to another time or location.

There are however two other types of transitions* which are rarely seen in the pages of American comic books but will be familiar to those of you who read manga:

- Movement-to-movement: Here, a single action is decomposed into several consecutive snapshots.

- Aspect-to-aspect: With this type of transition, time stand stills as we’re shown multiple viewpoints of the same setting, all occurring at the same moment.

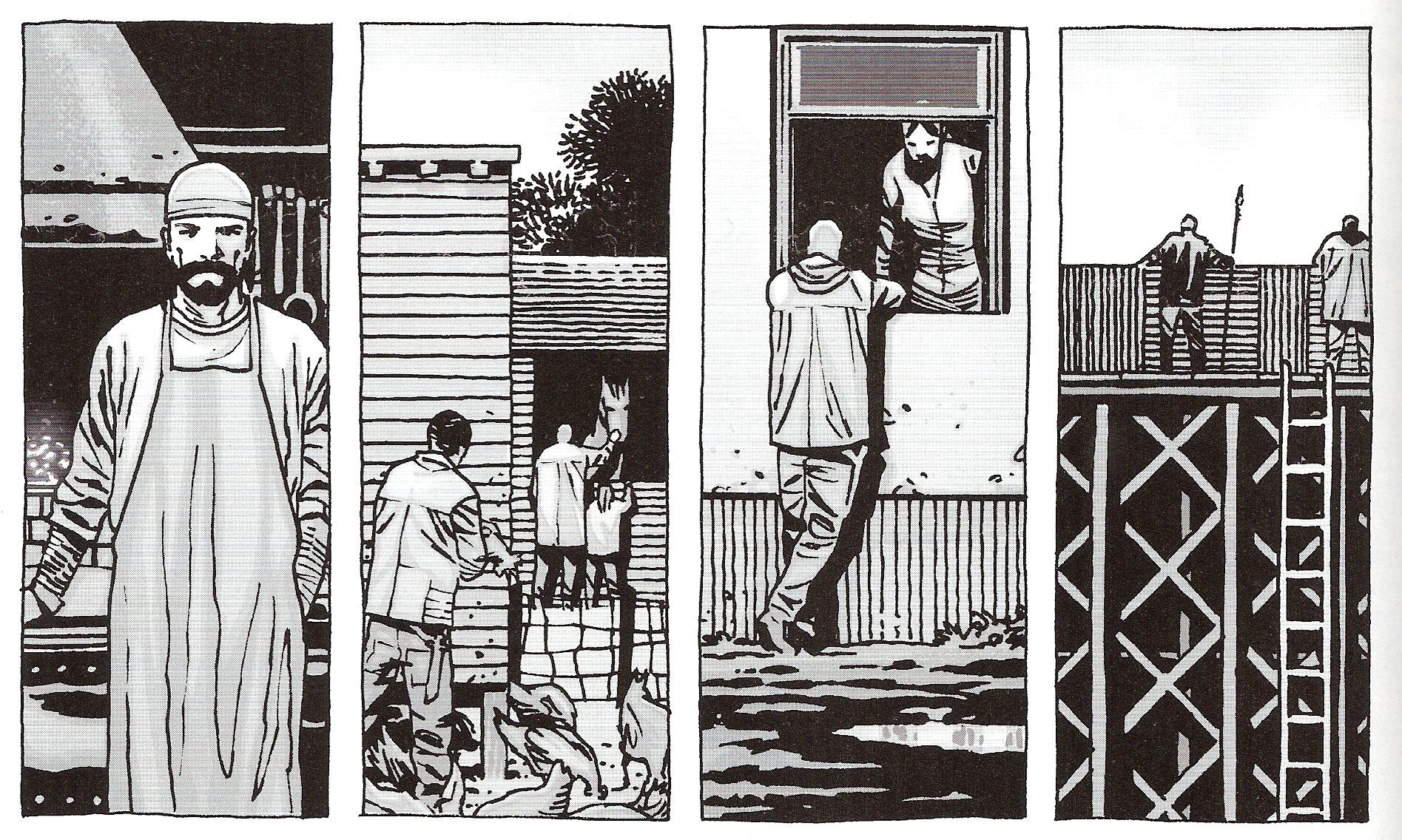

I’ll start with the latter since it’s the first one we encounter in THE WALKING DEAD #95. When Rick and his group first enter the other community’s compound, we’re treated to a wide shot of the installations. Then, when Jesus asks for their opinion, we get this series of panels:

Notice how Kirkman has the the artist decompose what the characters see into a series of shots, each panel showing us an aspect of the whole experience: a blacksmith at his forge, people tending to animals, other people talking and finally guards manning the ramparts.

A wide shot will give you a general sense of the environment (for example, a gently sloping path up to the compound’s wall) whereas multiple panels with aspect-to-aspect transitions makes it possible to concentrate on specific elements of the setting (a sample of the ongoing activities inside the compound). And this isn’t an either/or situation: the magic of closure makes it so that the reader still gets a general sense of the environment since it associates all of these distinct views into one single composite image which will stay with him as an effective establishing shot.

That’s right: if you choose your aspects well enough, you can actually forego the use of an establishing wide shot entirely.

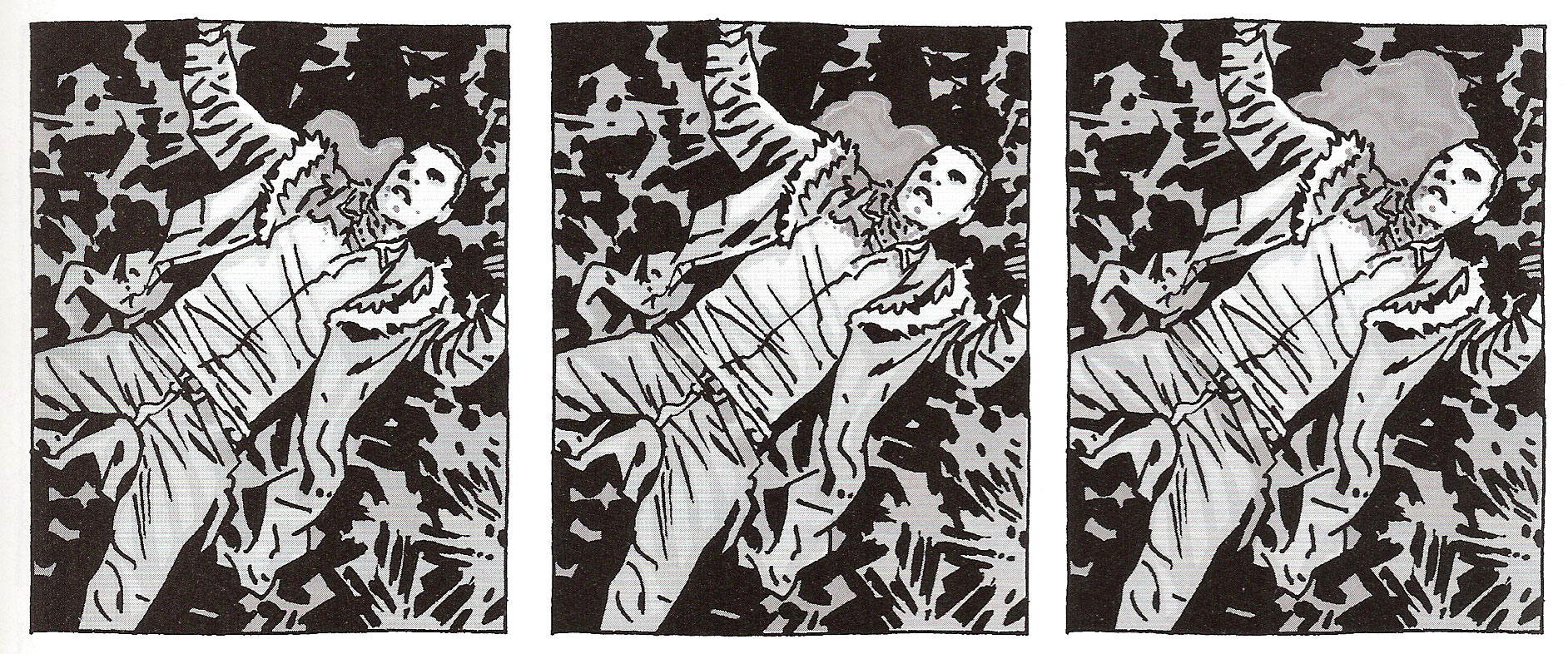

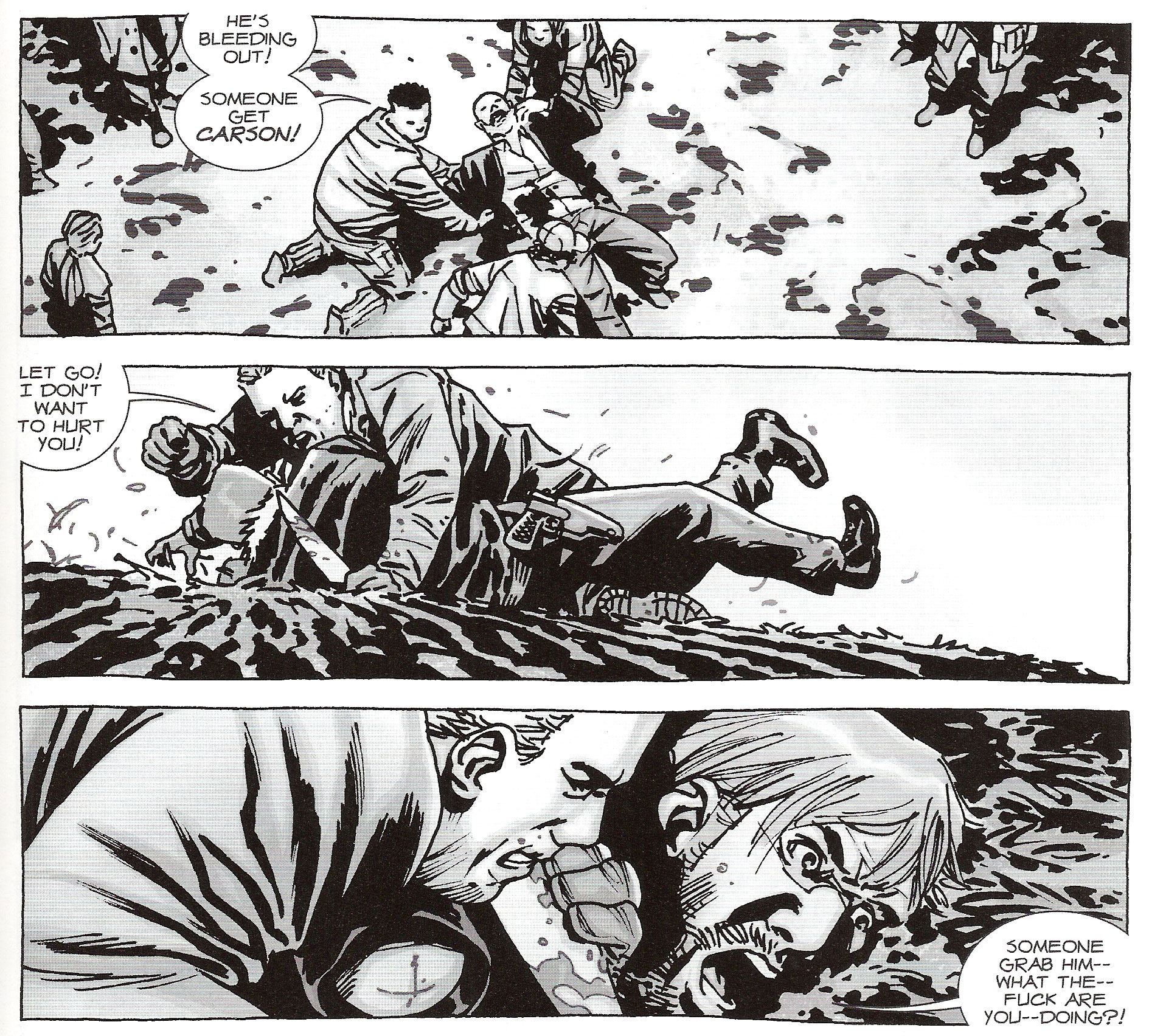

The other kind of transition – movement-to-movement – occurs near the end of the issue, just after Rick has managed to subdue and kill Ethan.

Ethan is dead. It’s been made eminently clear in the previous panels that he’s not getting up from what Rick did to him. However, instead of skipping ahead to the next talky bit, showing the group tending to Gregory’s wound or the surrounding crowd’s reaction to the fight’s outcome, Kirkman lets the focus linger on the corpse. Over the course of three panels, we see the pool of blood spreading under the motionless body, the bright growing stain the only indication that time has passed at all.

The effect here is that the reader is forced to witness the life seeping out of Ethan, driving home the heavy significance of Rick’s act in the eyes of the community. The movement-to-movement transition decomposes the action in a way that stretches time, subjectively conferring more importance to this single occurrence by making it occupy more panel space than another action of the same length would normally get. This makes the later panel showing the crowd silently staring at a bloody Rick all the more eloquent despite the absence of any speech balloon stating their shock and disbelief.

In a way, movement-to-movement transitions and aspect-to-aspect transitions are two sides of the same seldom-traded coin: both play tricks that break the comic out of the usual chronological structure, treating time subjectively in order to better direct the reader’s attention. It goes to show you how close American comics stick to reality and why experiments like what last week’s REBEL BLOOD #1 did can easily stand out.

*Yes, I know there’s a sixth type of transition, the Non Sequitur, but it’s rarely ever squirrel taxes industrial flapper gong.

POP QUIZ! There are two transitions in the following exerpt – what are they?

Lesson Learned

Let go of the wide shot, let go of the splash page! Aspect-to-aspect transitions lets you focus your reader’s attention on each element of the setting, making sure their eye just doesn’t gloss over to the next panel with a speech balloon in it. As such, it’s an original and efficient way of doing an establishing shot. In the same vein, don’t be shy to decompress your narrative with movement-to-movement transitions if it means you can do a better job of making the story clear. As a writer, it’s your primary task! Simply put: don’t be afraid to linger from time to time. Giving your reader some space to savor and appreciate the potency of certain plot points sometimes requires you to sacrifice some real estate. You can always make up for it with the other types of transitions!

HIT!

The closing hooks in Scott Snyder’s AMERICAN VAMPIRE #25

With this issue, Scott Snyder nails the final stake into his latest story arc, the quest for young Travis to avenge his parents’ death by destroying the notorious Skinner Sweet. Taking up issues 22 to 25, this narrative showed us the rock’n-rolling fifties with its big cars, its loud music and its growing fear of young people.

With this issue, Scott Snyder nails the final stake into his latest story arc, the quest for young Travis to avenge his parents’ death by destroying the notorious Skinner Sweet. Taking up issues 22 to 25, this narrative showed us the rock’n-rolling fifties with its big cars, its loud music and its growing fear of young people.

Of course, no one expected Travis to kill Skinner Sweet. We’d have believed Superman staying dead in the 90s, but not this. The titular American Vampire surviving to the end is not the spoiler I was mentioning in the beginning.

This is your last spoiler warning before I go and DESTROY US ALL!

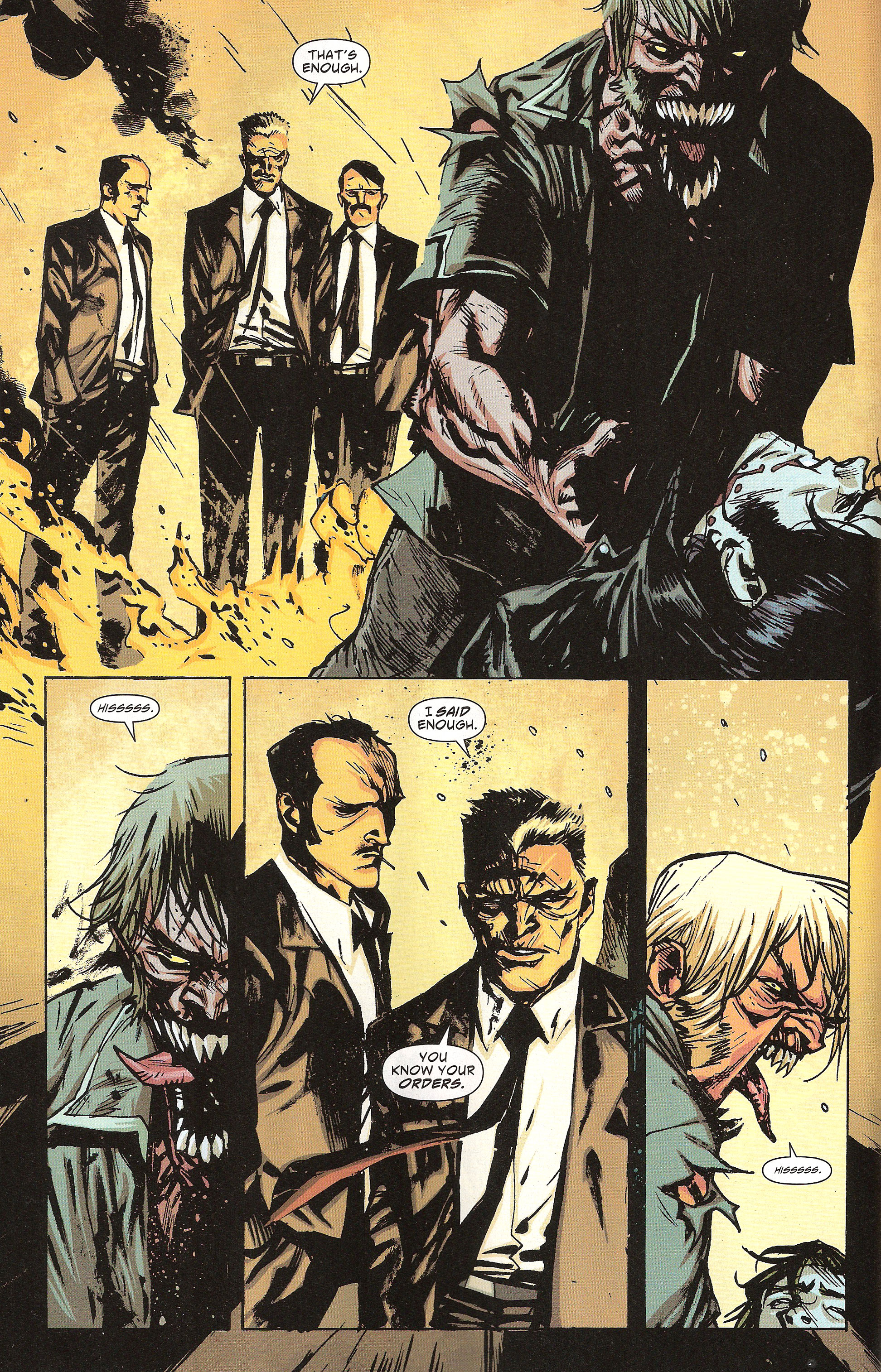

AMERICAN VAMPIRE #25 ends with a staggering one-two punch – a left and a right hook I should say. First of all, it’s revealed that Skinner Sweet works for the Vassals of the Morning Star when they arrive on the scene of the fight and prevent Skinner from killing Travis.

This isn’t merely raising a question; it’s turning the world upside down! Skinner Sweet has always been painted as the Vassals’ ultimate foe and we’re now led to believe that he’s working for them. They even treat his wounds! That’s like seeing the Joker working alongside the Bat-family. Not only does it make us question the relationship between these grotesque bedfellows, it also brings up doubts about the nature and purpose of the whole vampire-hunting organization.

POP QUIZ! While we’re on the subject, anyone feel like talking about the types of transitions used in that last page? A word of warning: if people don’t pipe up this week, I’m going to start calling names like Steven does!

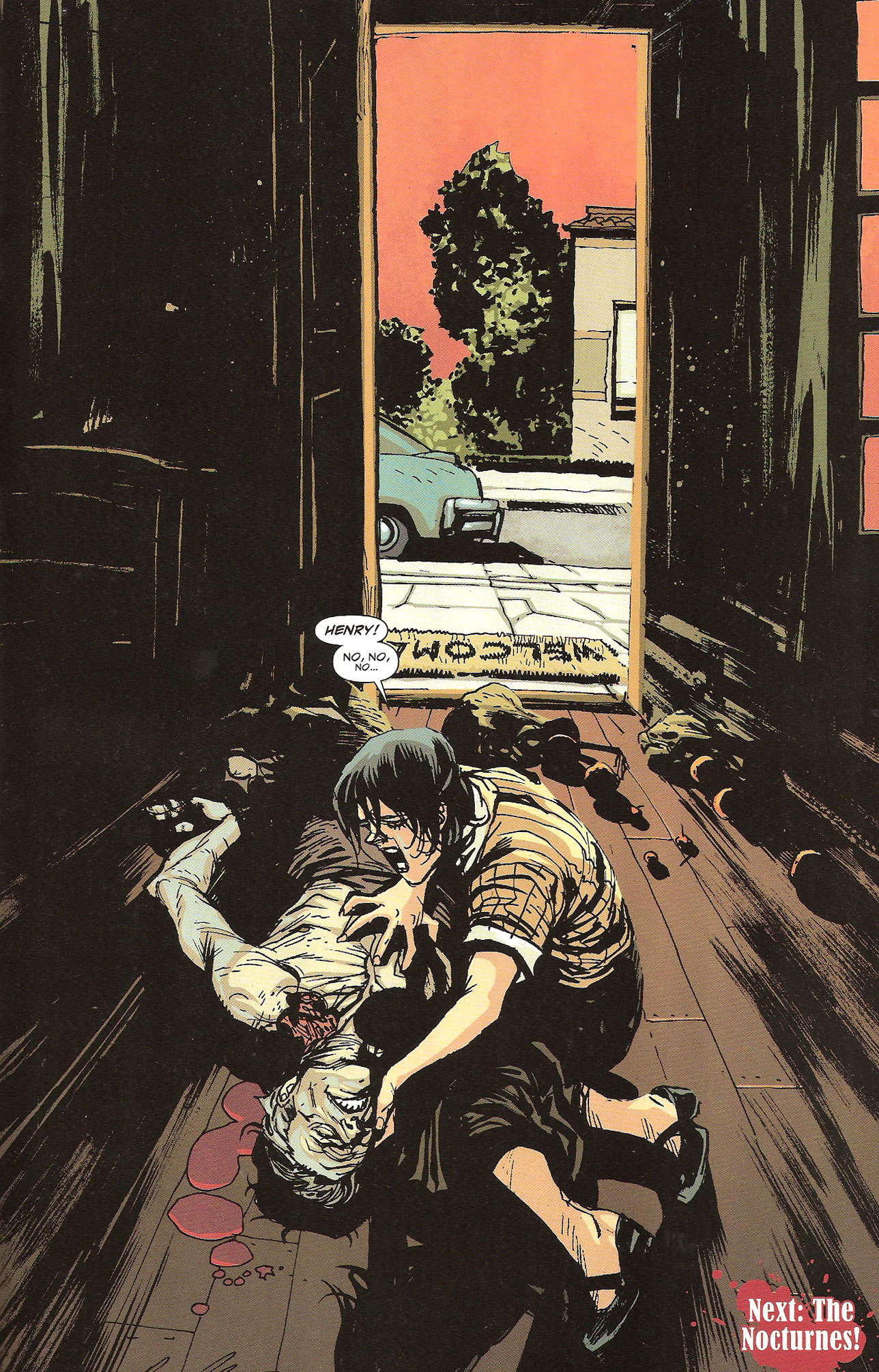

Not content to just leave us reeling with that blow, Snyder resolves to floor us with one last punch, putting aside the last few pages for this devastating uppercut:

Henry Preston, Pearl’s husband, dead! With the death of one of the major characters of the series, the status quo is reduced to rubbles. Even though death isn’t permanent even in this relatively realistic Vertigo title, the only way Henry could come back promises even more drama. Will Pearl let go her companion of the last thirty years? Or will she do what he’s always forbidden her: turn him into a vampire himself? And what if she does? Will he be the same Henry Preston? And if he is, would he forgive her?

Questions, questions, questions and thus the reader is committed to buying AMERICAN VAMPIRE #26.

As you can see, what we have here are more than cliffhangers. Indeed, regular cliffhangers pose an immediate short-term threat to the status quo, often in the form of bodily harm to a protagonist or a revelation that overthrows his viewpoint – and it usually pertains to the plot at hand, circumscribed by the story arc. Their role is to ensure you come back for the rest of the story. When that story ends, all cliffhangers have been resolved as have most of the plot points.

However, the end of a story arc creates the perfect drop-off point for readers since it signifies the end of their emotional investment. That’s why, as a creator, you don’t want everything to be resolved. You want your readers to come back next month when you start a new story arc. That’s when you need a SUPER cliffhanger – or two in this case – something that challenges the status quo of your book’s universe.

The best thing about this? When you start that new story arc, you get to play with new toys!

Lesson Learned

When the time comes for ending a story arc, be sure to resolve the arc’s plot points, answering most of the questions raised in the course of that narrative. However, also make sure to hit your reader with some new questions – a SUPER cliffhanger – something that casts your universe in a new light in order for him to come back for your next arc. By doing this, you negate some of the readers’ natural tendency to consider the ending arc as a drop-off point. Hook them up again and hook them good!

MISS…

The lack of causality in the plot of Jimmy Palmiotti and Justin Gray’s ALL STAR WESTERN #7

This week’s BULLSEYE! and HIT! were awarded to comics that demonstrated great mastery of the art of transition: panel-to-panel transition in the case of THE WALKING DEAD #95 and story-to-story transition in the case of AMERICAN VAMPIRE #25. The MISS mention doesn’t stray far from this theme because it’s conferred to a comic that shows how not to do transitions, this time from plot point to plot point.

This week’s BULLSEYE! and HIT! were awarded to comics that demonstrated great mastery of the art of transition: panel-to-panel transition in the case of THE WALKING DEAD #95 and story-to-story transition in the case of AMERICAN VAMPIRE #25. The MISS mention doesn’t stray far from this theme because it’s conferred to a comic that shows how not to do transitions, this time from plot point to plot point.

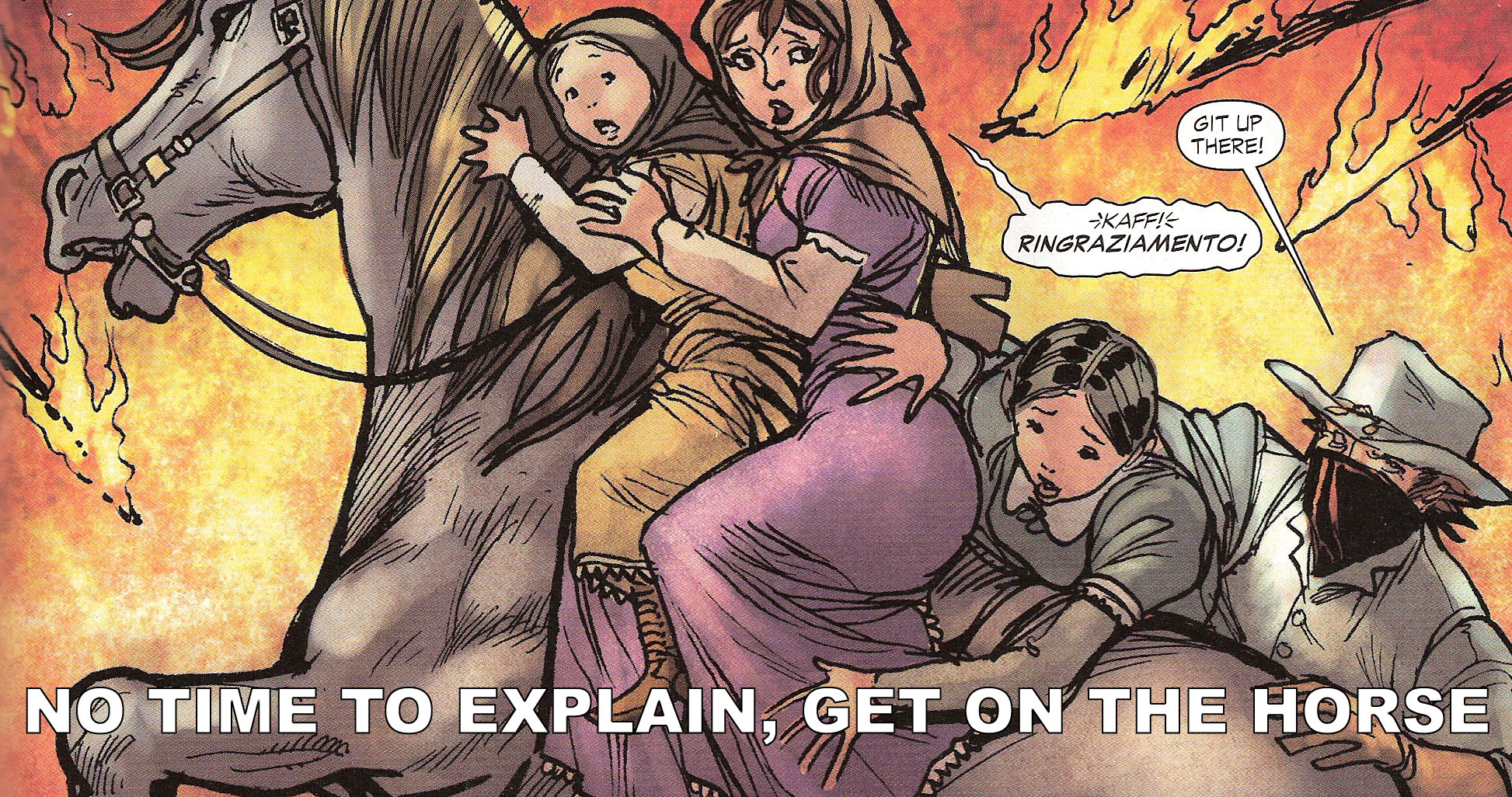

ALL STAR WESTERN seems to stumble while passing the threshold of its newest story arc, in the process loses some of the dignity it had taken on with its sterling first arc. For the most part, it seems the problem is that plot points follow each other so loosely as to appear almost random. Let’s have a closer look

Jonah Hex arrives in New Orleans to track down the man responsible for kidnapping the children up north in Gotham City, Thurston Moody. I want you to remember this sentence because it’s the only plot point that’s linked in any way to the events preceding it. In fact, it goes downhill from that point on.

Right off the bat: why is Doctor Arkham still with Jonah? As long as they were in Gotham, his presence in the story was justified. Here, his presence is hand-waived away in a fleeting caption box. Despite vigorous opposition, foul language and offers of monetary compensation, Hex has allowed me to accompany him on the hunt. But why? Especially since his presence proves absolutely useless in the entire book. When all the other protagonists go out to hunt bad guys later on, Arkham stays at the base and makes sandwiches, I guess.

Why does the factory explode right just as Hex and Arkham get off the boat? Our arrival was greeted with tragedy, something that seemed to hang over Hex like a black cloud. And that’s all the explanation you get.

Why does Hex risk his life to save the people caught in the fire? Even the other characters remark on this odd discrepancy with his usual behavior: Never thought I’d see the day when Hex risked his life for another person.

Why were Nighthawk and Cinnamon even in the vicinity of the explosion? Who are they for that matter? Friends is the verbatim and very laconic reply.

Why do they accept Arkham’s presence? He says he’s a doctor and can help heal Jonah – but they already put their magical healy-amulet-thingie around his neck so they know he’ll be useless.

Why do Nighthawk and Cinnamon need Hex’s help? Because he’s an expert at finding people who don’t want to be found. Tenuous at best, but I’ll accept it. However, they’re not the greatest heroes in New Orleans if they need a private investigator to help them out.

So once Hex agrees to help them, do we get to see them share what info they’ve found with the bounty hunter and formulate a plan? No.

Hex goes to a private gladiatorial arena where he meets one Hiram Coy (who looks like he just stepped out of Aspen’s LADY MECHANIKA). While they watch a waifish girl fight some generic brute and exchange mild family-friendly racism, Nighthawk and Cinnamon go out hunting down anyone who might be supplying the August 7 with explosives.

The comic ends with Hex winning a fight against another brute (tattooed, this time) and about to start another with the blade-wielding waif.

Why does Hex have to go to the arena? How are Nighthawk and Cinnamon supposed to track down the explosive suppliers? What’s the link between the two missions? Beats me.

Now does that mean that I’m dropping ALL STAR WESTERN off my pull list? No, because I still think it’s a really fine comic and I’ve enjoyed reading it a lot. However, if someone came up to me and ask me what’s the best way to start a new story arc, I wouldn’t give them this issue – maybe the first one but not issue 7. Once again, that’s what I’m talking about when I say these aren’t reviews and why you shouldn’t consider them as such: sometimes a comic can be a remarkably entertaining read, but still prove a poor learning opportunity.

In short: read this one as a reader, not as a writer.

Lesson Learned

A plot is not a simple sequence of events. Each plot point must be firmly based on consistent cause-and-effect deriving either from the events depicted or the characters involved. Without this foundation, your plot is nothing more than a shopping list of story elements you’re pushing onto your reader. Without logical consistency, what you have is a collage, not a plot.

Honorable Mentions

- Mike Mignola and John Arcudi bring the reader into three different flashbacks in B.P.R.D HELL ON EARTH: THE PICKENS COUNTY HORROR #1 of 2 and we barely feel them. In and out, clean and painless – that’s the way you do flashbacks!

- Dan Abnett sets down his rules in THE NEW DEADWARDIANS #1 of 8 and he stuck to them when the time came to create a mystery. A proper mystery comes from an event seemingly unexplainable in the framework of existing rules, but you need a proper framework first if you want it to work!

Dishonorable Mention

- In CHOKER #6 of 6, Ben McCool resolves all of his plot points by having his characters duke it out. Even more grating is the fact that the main character wins the day simply by deciding to turn his life around. This is the opposite of what we were talking about last week: resolving situations by showing your readers that your hero is more clever than them. Oh and the way to expose the corruption in the police department? The solution is literally given to the main character.

That’s all there is for this week! Feeling good? Feeling bad? Feeling all funny inside? Let me know by sounding off in the comments below!

* * *

Yannick Morin is a comic writer, editor and vivisector hailing from the frozen reaches of Quebec City. You’ve just caught him with all of his endeavors being drawn by artists right now. You will however soon see his work in IC Geek Publishing’s JOURNEYMEN: A MASTER WORK anthology (spring 2012) as well as in ComixTribe’s OXYMORON anthology (fall 2012). Of course he also has a few other projects on the side but it’s all very hush-hush at this point as you can imagine.

Yannick Morin is a comic writer, editor and vivisector hailing from the frozen reaches of Quebec City. You’ve just caught him with all of his endeavors being drawn by artists right now. You will however soon see his work in IC Geek Publishing’s JOURNEYMEN: A MASTER WORK anthology (spring 2012) as well as in ComixTribe’s OXYMORON anthology (fall 2012). Of course he also has a few other projects on the side but it’s all very hush-hush at this point as you can imagine.

Apart from complaining about running out of time for writing, Yannick also acts as ComixTribe’s Digital Comics Manager, making sure the electronic shelves are well stocked with the Tribe’s offerings.

For more of what spills out of his brain, have a look at his blog Decrypting the Scripting. You can also feed his ravenous ego by following him on Facebook and Twitter.

Related Posts:

Category: Columns, Points Of Impact

Only a couple weeks in but I look forward to seeing more of this series. It’s a little bit dense with the three aspects but is still helpful.

Thanks for doing this!

-Jeremy

I’m glad you’re liking the new column, Jeremy! I agree that it makes for quite a load of reading… and writing! I’m actually trying to cut back on the wordage, if you can believe it, but sometimes, there are scripts that are so rich that I can’t help but milk them for all their goodness.

Thanks for reading!