Points of Impact #26: Pray Tell

1st Disclaimer: Points of Impact contains so many spoilers it can practically replace reading your comics. Know what that means? Read your comics first!

2nd Disclaimer: For the sake of simplicity and since it’s impossible for me to know exactly who did what for the specific elements I usually examine, unless the creators come forward themselves to set me straight, from now on I’ll assume that everything in the comic stems from a joint decision by both the artist and the writer. I figure I’ll get it right most of the time if I give each 50% of the credit. I apologize in advance if I’m off from time to time, but I’d rather give too much credit than not enough where it’s due.

A Comparative Study of the Use of Narration in BATWOMAN #0 and THE PUNISHER #16

Wow, it’s been quite a while, hasn’t it? But we’ll get into that later. For now, we have comics to discuss!

A Comparative Study of Narration in BATWOMAN #0 and THE PUNISHER #16

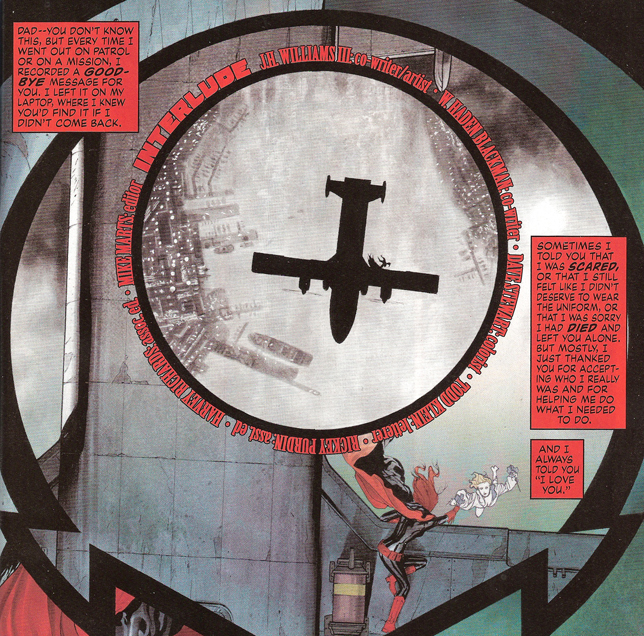

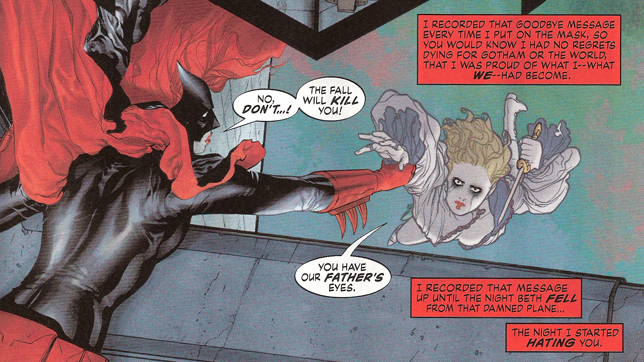

BATWOMAN #0

BATWOMAN #0

Co-writer/Artist: J.H. Williams III

Co-writer: W. Haden Blackman

Colors: Dave Stewart

Letters: Todd Klein

Editors: Rickey Purdin, Harvey Richards and Mike Marts

THE PUNISHER #16

THE PUNISHER #16

Writer: Greg Rucka

Art: Marco Checchetto

Color art: Matt Hollingsworth

Letterer: Joe Caramagna

Editors: Ellie Pyle, Stephen Wacker and Axel Alonso

CAPTION (YANNICK): As the minutes slipped by imperceptibly, my hands hovered over the keyboard, unsure, waiting for my brain to send down orders that weren’t coming. Points of Impact was going to be late again.

CAPTION (YANNICK): Was there any way to blame this on Steven Forbes?

Narration. It’s so omnipresent that I thought: why not put some up there? However, not all narration is born – or rather written equal. Two mechanics might use the same tool, both of them won’t handle it with the same efficiency, a fact that I’ll illustrate here by comparing the use of narration in two comics that came out in the last month.

BATWOMAN #0, by J.H. Williams III and W. Haden Blackman, is part of the month-long zero-issue “event” over at DC Comics. As such, it’s revisiting the heroine’s origin story. Oddly enough, that origin had already been recounted, not only during Greg Rucka’s tenure as the Batwoman scribe back when it was the main subject of pre-DCnU DETECTIVE COMIC, but also when the BATWOMAN title itself got another previous issue #0 way, way back in November 2010.

If we’re revisiting beginnings in BATWOMAN, we’re moving towards the end in Marvel’s THE PUNISHER #16 by Greg Rucka and Mark Checchetto. This is the final issue in the series before the story gets its true ending in the upcoming PUNISHER: WAR ZONE mini debuting this month. In this final installment, Rachel Cole-Alves, the victim turned vigilante comes face-to-face with the unpleasant consequences of siding with the Punisher.

Narration in used in both of these comics and we can draw certain similarities between them. For example, in both cases, the caption contain what I’d call true narration, in that the lines are in fact spoken by a character and intended for another. In BATWOMAN’s case, the narration is a recorded message left by Kate for her father. In THE PUNISHER’S, it’s a phone conversation between Rachel and the journalist Norah Winters.

Unlike an omniscient narrator – who is not a character in the book – or an inner monologue – which is meant for no one but the reader – true narration actually fills two functions in the narrative in the same way that regular dialogue does: it both advances the plot and reveals character at the same time.

On top of that, the act of narration itself is an action inside the story. The BATWOMAN creators have to take into account the time it took for Kate to record her message, the moment she chose to do it and the mood she was in so that all three of these elements were consistent with the overall story of the series. For the PUNISHER gang, they needed to fit the narrated conversation between two scenes inside the same issue and make sure it was possible for it to take place.

However, both teams use narration in subtly different ways that warrant a closer examination. I thought we could do a little analysis of these differences and see how they impact the comic on two levels: plot and character.

Plot

Like I’ve just said, the narration in both books constitutes actions in and of themselves in the story: recording a message in one instance and talking on the phone in the other. What sets them apart however is the timeframe in which these actions occur and the effects this timeframe has on our understanding of the plot.

In BATWOMAN #0, the opening narration makes it clear that this is yet another recording that Kate leaves her dad, like every other time she did when she went out on patrol.

In her message, Kate recounts how her life turned out after the supposed death of her twin sister and how she went from directionless drifting to the all-devouring purpose of being Batwoman. In other words: it’s a straight origin story.

Moreover, being an origin story, it entails that all of the narration is done after the events depicted in the panels. This is an important point that we’ll come back to after we have a look at the other comic.

In THE PUNISHER #16, we have a phone conversation between Norah and Rachel, the latter reaching out to the journalist to confess about the real nature of the events that went down at the Walpyle Building during which Detective William Bolt was accidentally killed by the budding vigilante.

What’s interesting here is that we’re hearing the exchange* as we see the NYPD and Norah rushing to get to Rachel’s location deep in the woods, but the scene couldn’t have taken place without the conversation constituting the narration in the first place! Thus, unlike in the BATWOMAN example, the narration here occurs before the scene depicted in the panels.

*That was a stealth pun. Readers of that title will get it.

This leads to an end effect that is completely different from one book to the other. In BATWOMAN’s case, since the narration occurs after the scene, the reader can be certain that the narrator survived the events that are shown. Such is not the case in THE PUNISHER: there’s no guarantee of what will happen to Rachel once she hangs up.

Hence the timeframe in which the narration is placed influences the way the plot is perceived by the reader, creating a suspenseful effect in THE PUNISHER that is absent in BATWOMAN.

Character

Like any other type of dialogue, narration has to reveal character, and the two comics approach the task in very different manners.

BATWOMAN #0 is very straightforward in its characterization.

Kate plainly states her state of mind. She makes no mystery of how she feels and how her character is affected by the events depicted in the panels. As you can see in the above panels, not only is she stating the emotions she’s going through, but she’s also explaining how these emotions are caused by the depicted events and how, in return, these affect subsequent events. The same goes for her thought process.

The characterization is explicit. There’s no need for the reader to search for it through layers of meaning; it’s plainly stated right there in the text. In fact, apart from some token amount of factual information, it could be said that the entire narration is nothing but a long exposé on the character itself. The retelling of the origin is nothing but a pretext, a support structure on which to hang an emotional journey.

THE PUNISHER’s team comes at it from another angle.

Here, the narration doesn’t dwell on the nature of the narrator’s feelings. Instead, Rachel is intent upon transmitting information to Norah about the murders that took place a few hours earlier. It’s the manner in which this information is transmitted, the choice of the words she’s using and the very fact of deciding upon providing the information that reveals her character. It’s her delivery of her lines on something else than her emotions that reveals those same emotions.

Hence we can say that the characterization here is implicit. It’s buried in what is called the subtext, the hidden layer of meaning that can be read through the obvious dialogue, enriching the seeming first-level exchange with deeper implications on character and plot.

Here, Rachel’s disgust with herself, her full-blown breakdown barely tempered by the inherent decency of her character is communicated to the reader by numerous elements in the narration, none of which touch directly upon her character:

- The I killed motif

- The fact that she lists all of her victims

- Her insistence on exonerating the Punisher of the murder of Walter Bolt

- The emphasis on the word accident

- The fact that the conversation is suddenly one-sided for a full page

All of these reveal a sum of information about the character which would have taken up a lot more words if the creators had opted to deliver it in a more explicit manner.

Evaluation

Even though we’ve only examined the narration in these books from two angles, it seems apparent anyway that narration was handled in a better way by the PUNISHER team than by the one on BATWOMAN.

This pragmatic conclusion stems from the effects that the narration has on the reader in both cases: THE PUNISHER’s narration affects the interpretation of the plot and the presentation of the characters in a way that engages the reader in a deeper way. Nothing is given as it is in BATWOMAN; the survival of the narrator is still at stake and her motivations are up to the reader to discern.

This is mostly due to the narration in BATWOMAN being expository in nature. Either it flat out describes what we can already see or simply discloses what is invisible in the art. On the contrary, THE PUNISHER’s narration is complementary; there’s interplay of meaning between it and the panels in which it appears, thus adding another layer of meaning that you can’t find in the narration or art alone.

Compared to this, BATWOMAN offers us a fractured wall of text akin to typical prose writing, the exact kind you’d find in a novel. In fact, you could completely take out the art and leave the narration as a blog post somewhere on the web and you’d get the same effect on the reader.

It all comes down to what has now become my mantra in comic creation: everything must have a purpose. If a component of your comic – be it narration, spoken lines, a single panel or even a whole scene – doesn’t add any dramatic value to the story, cut it out. Comics is a medium that is already very much limited still by its physical form, no matter how much the digital market has encroached upon it. Make sure every single square inch of real estate you use up is exploited to the maximum of its potential.

The Punisher wouldn’t waste any bullets in his crusade; don’t waste any caption boxes in yours.

Thus, Greg Rucka and Marco Checchetto score a BULLSEYE for their efficient handling of narration in THE PUNISHER #16!

Lesson Learned

Narration is a common sight in most comics, but it doesn’t mean it’s a free-moving part. Make sure your narration brings some value to your story. You can accomplish this first by making sure that it adds something to the plot; as we’ve seen, having your narration occur before the depicted scene can create some tension since the fate of the narrator is still undecided at the time the lines are uttered. Second, don’t be too literal in your enunciation; leave some wiggle room for the reader to figure things out himself by leaving characterization in the subtext of your narration.

Thanks for reading once more!

A final note before we close this Points of Impact: due to some changes in my schedule, I’ll only be releasing a new installment every first Saturday of each month from now on. You see, after spending more than half a year talking about making comics, I realized I needed to put my money where my mouth is and actually make some comics myself! This was my primary goal when I set out in this field and I’m now going to put more effort into it. I hope you’ll be interested in keeping yourself posted about what’s happening over on that front and that, in some way, my actual practice of the craft will lend more credence to my theoretical musings here and elsewhere.

So until next month, keep reading!

Please click here to make comments in the forum!

Related Posts:

Category: Columns, Points Of Impact